The Equity Partner You Don’t Realize You Have

By David A. Smith

6 min read

If you own an income-producing property, you have an equity partner hiding in plain sight. Despite never signing a document with you, your municipality owns somewhere between one-eighth and one-quarter of your property’s economics, a slice it can increase without your consent, and will own longer than you’ll own the property.

Once you see this, you can’t unsee it. I’ll state it, prove it to you and then we can delve into its manifold implications.

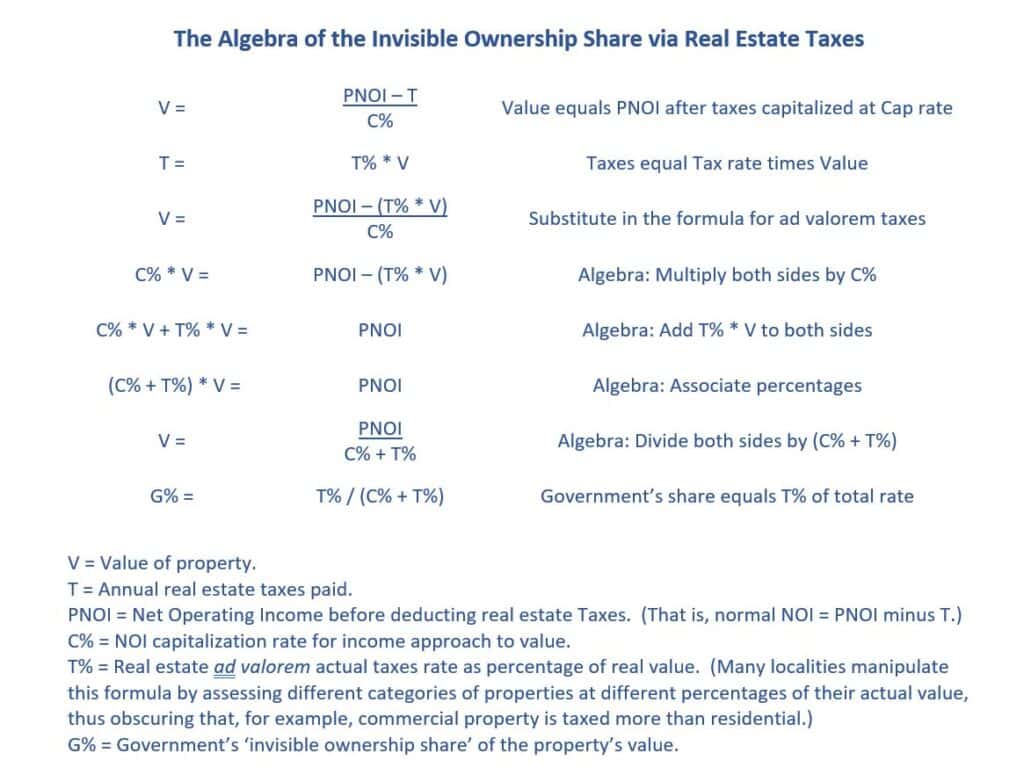

The formula. If you own income-producing property subject to ad valorem real estate taxes at a rate of T percent of actual value, and whose value can be expressed as a cap rate of C percent of Net Operating Income (NOI) after real estate taxes, then the municipality’s economic ownership share is T% / (T% + C%). Thus, if real estate taxes are 1.25 percent of value, and NOI cap rates are five percent, the municipality owns 20 percent [1.25% / (1.25% + 5%)] of the deal’s economics.

That can’t be right, thinks the reader.

The algebraic proof. Haul out your high-school math textbook and follow along with the inset box. When I first did this, something like 45 years ago, I didn’t believe my own algebra, so I built a program (it was before electronic spreadsheets, not even VisiCalc) to compute it, and have replicated it in Excel.

Now that we’ve proven that real estate taxes are, in fact, a meaningful equity position, what does holding this stake imply for a municipality’s standing, incentives and behaviors?

The equity position. As an equity slice of ownership, the municipality is uniquely desirable:

- It appreciates in value. As property values rise, the real estate taxes rise alongside them, as long as the municipality’s not asleep and revalues the property every year.

- It primes every other creditor. Real estate taxes are paid ahead of any cash flow distributions and are collateralized by the real estate itself, ahead of the first mortgagee. Even the Federal government bows to the municipality’s economics – a real estate tax foreclosure can wipe out Low Income Housing Tax Credit restrictions.

- The equity position gets increased cash annually even on unrealized appreciation. The municipality can reassess a property’s upward value even if the owner has not tapped the hypothetical equity appreciation. (This is even more of a perverse outcome for homeowners on fixed incomes that can be priced out of their homes through the inability to pay the city-raised real estate taxes.)

- The city’s phantom equity ownership rises when interest rates fall. For income-producing properties, when cap rates fall, say because interest rates are cut, property values rise and real estate taxes will rise with them.

- …Sometimes without any increase in Net Operating Income (NOI). Rising resale value due to lower cap rates without NOI increases will consume a larger chunk of that NOI, cutting into the owner’s cash flow or debt service coverage margin. In extreme cases, they can push a previously healthy property into a deficit.

- It falls in bad times. When property values fall, the real estate taxes fall along with them – at least, they do if the municipality is reassessing to fair market value or if the owner successfully appeals a too-high assessment.

- …Or does it? Despite the foregoing, most municipalities that are thoroughly content to expand their budgets on the rising tide of property appreciation find it curiously difficult to shrink those same budgets when the property-value tide goes out, justifying it with all sorts of handy rationalizations.

In short, the municipality’s equity share is in a bulletproof first position in the capital stack, with an upside that’s paid currently even if unrealized by the owner: what’s not to like?

The public-policy consequences. An equity partner should co-invest alongside the operating partner, and in a visceral way municipalities understand this, as evidenced by their choices for spending.

- Shared services that benefit property owners. Local taxes pay for local police, fire and often the local hospital – all services that are essential for city inhabitants, especially home and business owners. Public schools are a special case of municipal services, in that they benefit homeowners (who do pay real estate taxes) and renters (who do not, though their landlords do), occasionally leading to shortsighted, and faintly offensive, local commentary opposing apartments on the grounds that the newcomer large families will overcrowd the schools.

- Public physical infrastructure as municipal land development to attract new property-tax-paying new construction. Local roads and utilities (principally electricity, water and sewer, and sometimes, natural gas) are understood as the public trunk infrastructure that complements the private property and its site infrastructure.

- Tax Increment Financing (TIF) has an explicit connection between property development and its tax revenues. Like PACE, TIF is predicated on the expectation that capital expenditures can pay for themselves, but unlike PACE, in TIF the payor and beneficiary are aligned. The city sells bonds on its full faith and credit, the money to be used to fund infrastructure connected with particular property developments, and as additional collateral pledges the increase in real estate tax revenues deriving from the increased property value on the identified sites.

- Affordable housing that captures a real estate tax exemption. Seen with the tunnel vision of a city that must balance its budget, a property that is fully tax-exempt a ‘free rider’ on the city’s infrastructure. That this housing is essential to a sustainable community, to say nothing of being inclusive rather than exclusive, often escapes the city council’s notice.

For affordable housing participants. Municipalities are a property owner’s shadow partners – whether they know it or not, and whether you know it or not. In fact, in many ways, they are the most important equity partner an owner will have because the relationship will last longer than the ownership does. Every transaction, assessment, appeal, improvement on the property and improvement in the surrounding area – each one of these things influences the owner’s property values and viability, and the municipality’s benefits and costs. Wise are the affordable housing developers and owners who continually reinvest in that relationship, and always explain its practical implications to stakeholders, opinion leaders, the media, and most especially, municipal officials whether elected, appointed or administrative.

PACE Financing is Riskier than

Many People Think

When first popularized two decades back, the Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) model, which stapled the required PACE debt service onto the real estate tax bill, was touted as “an innovative mechanism for financing energy efficiency and renewable energy improvements on private property,” the claim often being made that the program paid for itself. That would be true if the capital improvements worked as advertised and their projected savings were realized and endured. If not, the increase in real estate taxes resulting from the PACE debt service could bite the owner. The Department of Energy website blandly notes that “nonpayment generally results in the same set of repercussions as the failure to pay any other portion of a property tax bill” – that is, foreclosure.