Battalions of Sorrows: Part 2, The Curse of Double Bottom Line

By David A. Smith

6 min read

As shown in last month’s Part 1, the economically botched management of the 2020-2021 COVID pandemic precipitated the inevitable return of inflation. Though the household damage was palliated by enormous federal spending across two administrations, that cumulative largesse has now assured us that we will worry about inflation and deal with its consequences for at least the rest of the decade.

Warning: This takes quite some getting used to.

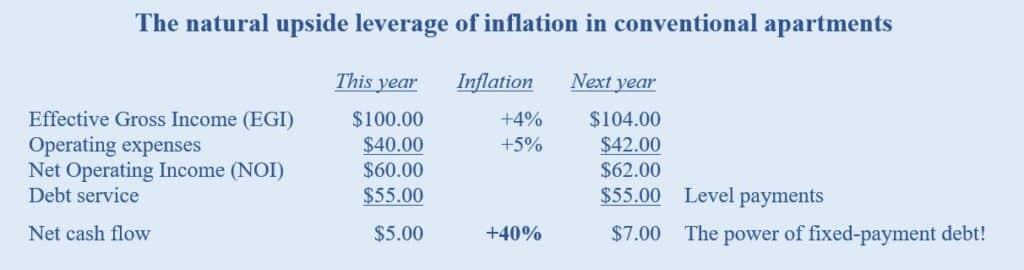

Though inflation always hits a property’s expenses before it lifts a property’s income, it is silently cheered by owners of conventional apartments. They are well enough capitalized and liquid to ride out the immediate expense shocks, while patiently anticipating the cumulative uproll of slow and steady rent increases. Because their operating expenses are seldom more than 40 percent of market Effective Gross Income (EGI), equal percentage increases in both boost Net Operating Income (NOI) proportionally and boost property cash flow more than proportionally, as shown in the sidebar.

Affordable housing owners and managers are less sanguine by far. Though hit with the same cost increases impacting conventional owners, their properties were underwritten to aim for lower NOI relative to EGI, so they have much less natural cushioning. Worse still, affordable housing owners suffer the curse of the double bottom line: though their operating costs rise to match the market just as fast as conventional owners do, their income can’t.

Leases, the Department of Housing and Urban Development regulations (and Operating Cost Adjustment Factors), subsidy limits, pledges made at the Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP) stage to win Low Income Housing Tax Credit awards, and statutory caps on LIHTC rents – the entire system is arranged to slow down the timing of owners’ rent increases and water down the amount when the increase does arrive.

Now, owners are coping with challenges across the entire operating expense budget:

Staffing. Property management is people-intensive – especially in affordable housing. All the digital information and smart systems in the world, correctly embraced as our industry scaled and became more administratively complicated, are no substitute for human site workers. In the paranoiac months right after the initial lockdown mandates, with the media warning that human contact could be fatal, their value skyrocketed. Unvaccinated, they went to work five days a week, often on public transportation, dealing with person-to-person encounters of every sort while their superiors were conveniently able to work remotely. Day after day of onsite stress burned many of them out, especially when inflation heated up in the reopening economy and they saw their household budgets being squeezed. The result was staff turnover: in 2022 and 2023, one regional nonprofit owner I know experienced 73 percent and 70 percent annually. Though new site staff were hired, at 25 percent higher wages than pre-COVID, “we pay more for less and can’t keep up with training.”

Maintenance. In terms of construction costs and building materials, the first few months after the lockdown brought not inflation but price explosions: for instance, lumber was up over 250 percent, if contractors could get it. At other times sheetrock/drywall was simply unavailable. While today’s lumber price is down 62 percent from its nosebleed high, that’s still 25 percent higher than pre-COVID levels. Such past shocks, and the likelihood of future shocks in the cost of, well, just about everything a property owner needs, have by now been permanently priced into the cost of new homes, resulting in a drop in new starts to the lowest level since COVID. Yardi Matrix shows repairs and maintenance up 8.3 percent year over year, and I expect that rate of increase to continue.

Real estate taxes. When it comes to real estate taxes, municipalities are in the catbird’s seat and property owners are locked in the trunk. When property owners construct their operating budgets, they must fit their costs within EGI that is capped by market or regulatory factors and have to tighten their belts. Municipalities pleasantly reverse the process: first, they eat, then they loosen their belts to accommodate their expanded girth. This is not always apparent, because total taxes are the product of assessed valuations times millage rates. In good times, when property values are rising, they can marginally lower the millage rate, announcing that they are ‘cutting taxes’ even as each homeowner is paying more. Conversely, when the economy contracts and the municipality’s other sources of revenue dry up, the municipality must preserve its cost budget, mustn’t it? Essential services are essential, aren’t they?—and all municipal services are essential, aren’t they?—and, however reluctantly, raise the millage rate.

Any ensuing increase in real estate tax burden usually falls more heavily on commercial properties than on homeowners (for reasons of the soundest political self-interest). Most affordable housing properties are deemed fully commercial (at least for real estate taxation), though a lucky fraction of affordable housing properties are insulated from abrupt real estate tax hikes because they were able to negotiate up-front tax abatements or outright tax exemptions.

No relief for the double-bottom-line owner. Despite these cost increases not of their making, up 35 percent over pre-COVID levels, the petitions of squeezed owners have so far fallen on sympathetic but inert ears. The self-appointed stakeholders of media, local officials and some resident advocates, believe that large owners and managers will find a way (which, in the generally benign economic environment since the near-death experience of 2008, they always have). As a result, the industry’s ‘friends’ have prioritized tenants’ inflation-induced problems, rather than helping the owners.

Now will the owners’ squeeze abate? Every cost I’ve listed—staffing, maintenance, real estate taxes and insurance (covered in Battalions of Sorrow: Part 1, Insurance)—will continue rising faster than baseline inflation.

And there’s a new cost horseman on the loose, a creature of the stakeholders’ COVID-relief impulses, and it’s the most epidemic of them all. I’ll cover it in my next column, and for now, will leave readers with an Oscar Wilde-inspired question: for double-bottom-line owners, what is the only thing worse than evicting tenants?