The Budget Brouhaha: Step-by-Step Through the Annual Government Funding Process

By Marty Bell

8 min read

On the first Monday in February each year, the day on which what is generally referred to as “the President’s Budget” is released, Washington is sated with that giddiness you feel on the night of a Nats’ playoff game or an all-star holiday concert on the Mall. After all, the federal government is the biggest bank in America and there are a whole lot of folks eager to dip into its coffers.

But in reality, the so called “President’s budget” is:

- only a request;

- only the halfway point in a fight for funds among millions of bidders;

- only really involves about 13 percent of the total federal budget since 65 percent of the current budget is mandatory, six percent pays interest on federal debt, and of the remaining 29 percent more than half is spent on the military;

- only an outline since even when the doling out is approved and the funding is appropriated, the decision about how it is to be spent is not binding.

There was no federal budget at all until 1921 when Warren G. Harding insisted upon it as part of his “return to normalcy” campaign following World War I (a campaign that earned him the biggest landslide in Presidential electoral history). And there was no process for negotiating a budget until 1974 when Richard Nixon tried to impound appropriated funds for benefits programs and so Congress passed the Congressional Budget Impoundment and Control Act that Nixon had to sign because he was in the midst of the impeachment process and the last thing he could afford to do was alienate the legislators.

Though there have been some addendums since the Watergate Era—such as sequestration for a few recent years when the branches of government could not agree on a funding plan—the process has remained fairly steady.

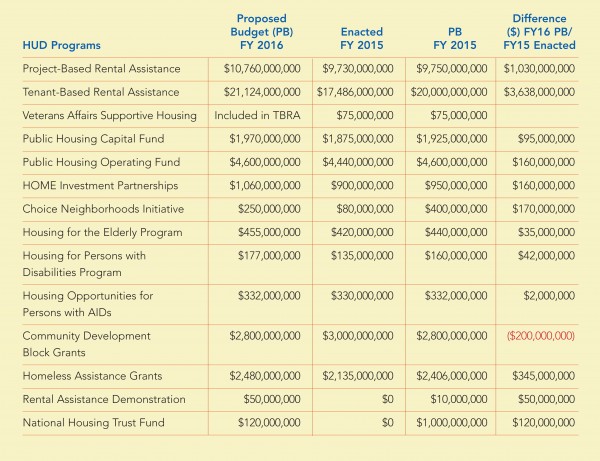

Though the FY2016 budget includes significant additional funding for HUD and good news for those in tax credit-financed development, don’t get overexcited just yet. Approval of these proposals has a long road ahead.

We thought it would be of value to walk you through the process and provide a sense of what you can expect and when.

Prior to the President’s Budget Release

Our government’s fiscal year runs from October 1 to September 30. But planning for the budget to be implemented next October began in the October two years prior.

Between October 2013 and February 2014, government departments and agencies worked internally to outline what they would like to do in FY 2016 and to estimate resultant costs.

Then between March and May of last year, still a year and a half from implementation, the departments presented their plan to the White House Office of Management and Budget, originally set up in the Harding era as the Bureau of the Budget, to try to conform budgetary requests with the President’s policies.

Between June and August, in between summer breaks, the agencies finalized their proposals and submitted them to OMB so that negotiations could begin when the government returned to full speed in September with the aim of providing the President with a budget he was contented to present in the required period, between the first Monday of January and the first Monday of February (though no one can remember a budget presented prior to the deadline).

Though there is no rule specifying timing, the President generally presents his policy initiatives to a joint session of Congress in his State of the Union address in January prior to releasing the budget for these initiatives early in February.

Budget Release and Budget Resolution

On the day the President releases his budget requests, they have already been through, and are the result of, 18 months of discussion and negotiation amongst thousands of people in the departments, often the issue experts, who will be charged with utilizing the funds. And only then are these requests turned over to Congress, specifically to the Budget Committees in both the House and the Senate.

Currently the House Budget Committee is chaired by Rep. Tom Price (R-GA) and the Ranking Member is Rep. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD).

Currently the Senate Budget Committee is chaired by Sen. Mike Enzi (R-UT) and the Ranking Member is Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-VT).

Other Congressional committees with budget authority will send their requests and priorities to the two budget committees. The role of Congress is to try to pass a Budget Resolution by April 15. The Budget Resolution will be the approved total federal budget by both houses of Congress.

The process to reaching a Budget Resolution is:

- The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, created as part of the response to Nixon’s impoundment of funds in 1974, analyzes the budget in March looking at the effects of the current budget over the next ten years.

- The CBO presents its reports to the House and

Senate Budget Committees which each can submit a budget resolution to their house by April 1. Budget resolutions are not mandatory and the committees can forego this opportunity.

- If the two resolutions differ, a conference committee comprised of representatives from both houses attempts to reach Concurrent Budget Resolutions. Unlike Joint Resolutions, Concurrent Resolutions do not go to the desk of the President for signature. Therefore, Concurrent Resolutions, unlike laws, are not binding.

- In 2002, 2004, 2007, 2011, 2012 and 2013 no budget resolution could be agreed upon. In those cases, instead of a resolution regarding the new budget, a Continuing Resolution was passed that continued to fund the government at the levels from the last passed Budget Resolution.

Authorization and Appropriation

What the Budget Resolution accomplishes is presenting an outline for and agreement on overall spending, approval of programs to be funded and the overall funding level for the departments and agencies. But it does not determine the individual spending for each program within each department. That is determined during the Appropriations process.

Each house of Congress has an Appropriations Committee.

Currently the House Appropriations Committee is chaired by Rep. Hal Rogers (R-KY) and the Ranking Member is Rep. Nita Lowey (D-NY). The Senate Appropriations Committee is chaired by Sen. Thad Cochran (R-MS) and the Ranking Member is Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-MD).

The Appropriations Committees each have 12 subcommittees that deal with specific parts of the budget. The subcommittee focused on the HECM program is the Transportation, Housing and Urban Development Subcommittee.

The chair of that subcommittee in the Senate is Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) and the Ranking Member is Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI).

The chair of that subcommittee in the House is Rep. Mario Diaz-Ballart (R-FL) and the Ranking Member is Rep. David Price (D-NC).

It is in these subcommittees where the work that most specifically affects our industry is done. After the budget resolution is passed, the subcommittees will hold hearings and each will draft an Appropriations Bill determining funding levels of individual programs (i.e., housing counseling) based on the overall budget. According to the Constitution, spending bills must originate in the House, which considers its Appropriations Committee and subcommittee bills beginning May 15.

Sometimes the 12 subcommittee bills are each considered and voted upon individually. At other times, some or all of the bills are combined into an Omnibus Bill for a vote. In FY 2015, for example, 11 of the sub-committee bills were joined in an Omnibus and only the Homeland Security bill was considered individually.

Once the House approves Appropriations, the process officially turns to the Senate (which has in actuality been doing its own appropriations work simultaneously). Over the summer, the Senate subcommittees review the House bills and send their own bills to the Senate floor for a debate and approval. If there are differences between the two houses’ appropriations bills, a reconciliation process is the next step

Reconciliation

If the two houses of Congress have differences in specific areas, they pass a Concurrent Resolution that instructs specific subcommittees to reconsider their bills. The subcommittees send their changes to the Budget committees of their houses, who combine them all into one Reconciliation Bill.

The Reconciliation Bill is voted on by the House first, then goes to the Senate where it requires 51 votes for passage. No filibustering of Reconciliation Bills is permitted. And there can only be one Reconciliation Bill in a session.

Conclusion

By the time an Appropriations Bill reaches the President’s desk for his signature (and in some years it does not), it has been developed, debated, and most likely diluted for two years by input from thousands of government workers. And all of this time has been devoted to only discretionary spending, which comprises only 29 percent of the total budget. And somewhere around 55 percent of that 29 percent is defense spending. So really what all of these people have spent the past two years on is negotiating about 13 percent of the federal budget.

Prior to the passage of the 1974 Budget Act and its creation of the Congressional Budget Office, the President had much more influence on the nation’s annual budget. But the last 40 years, beginning with Nixon’s tenure, has seen an ongoing dilution of Presidential budget authority and a steady drift towards a more serpentine appropriation and authorization process.