Housing USA

By Scott Beyer

6 min read

2023 Fair Market Rents Jump Amid Data Collection Changes

Late in 2021, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), using different than normal data, changed the way it determined Fair Market Rents (FMRs). FMRs are the gross rent estimate (base rent plus utilities) that are determined for different U.S. markets.

As HUD explains, the figures “represent the cost to rent a moderately-priced dwelling unit in the local housing market,” and that price informs how much a Section 8 voucher can provide in the area.

FMRs are important to affordable housing in a few ways, says Thomas Stagg, an accountant, and partner with Novogradac & Company LLP. Housing authorities can adjust the FMR a maximum of ten percent either up or down based on fluctuating local home costs. FMRs are used to broaden the scope of individuals able to receive housing assistance through the “high housing cost adjustment,” Stagg says, “in areas where rents are a high portion of tenants’ income.”

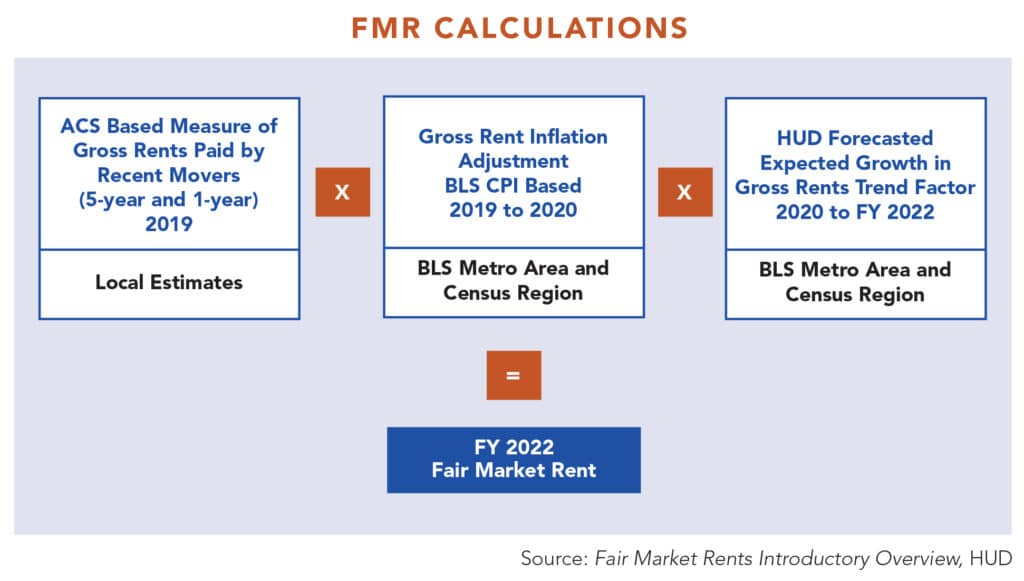

According to a HUD presentation (FY 2023 Fair Market Rents Briefing), FMRs are derived from “a standard quality (SQ) gross rent” based on American Community Survey five-year data, as well as overall patterns in rent, inflation and “recent mover” rents. They’re also used to determine public housing “flat rents” and some specifically targeted programs, such as “rent ceilings for rental units in both the HOME Investment Partnerships program and the Emergency Solution Grants program.”

FMRs are, thus, a key part of providing those in need with “safe, decent and sanitary” homes, Stagg says, noting that it targets the lower 40th percentile of rents.

But recognizing that the COVID-19 pandemic had a confounding effect on how rents should be determined, last year HUD announced a change to methodology. As the presentation states, the sample used to discern FMRs, the one-year American Community Survey, was not released in 2021 due to the pandemic, citing “high volatility in the rental housing market.” So, HUD settled on private sector data, such as from property value aggregator Zillow, listing site Rent List and Moody’s. The measure is temporary, only applying to the most recent FMR calculation.

Such data is “arguably timelier than what the state or federal government is able to collect,” says Anne Stanley, communications manager for the San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development. “Our news sources locally rely pretty heavily on those private market datasets,” adds Lydia Ely, the office’s deputy housing director.

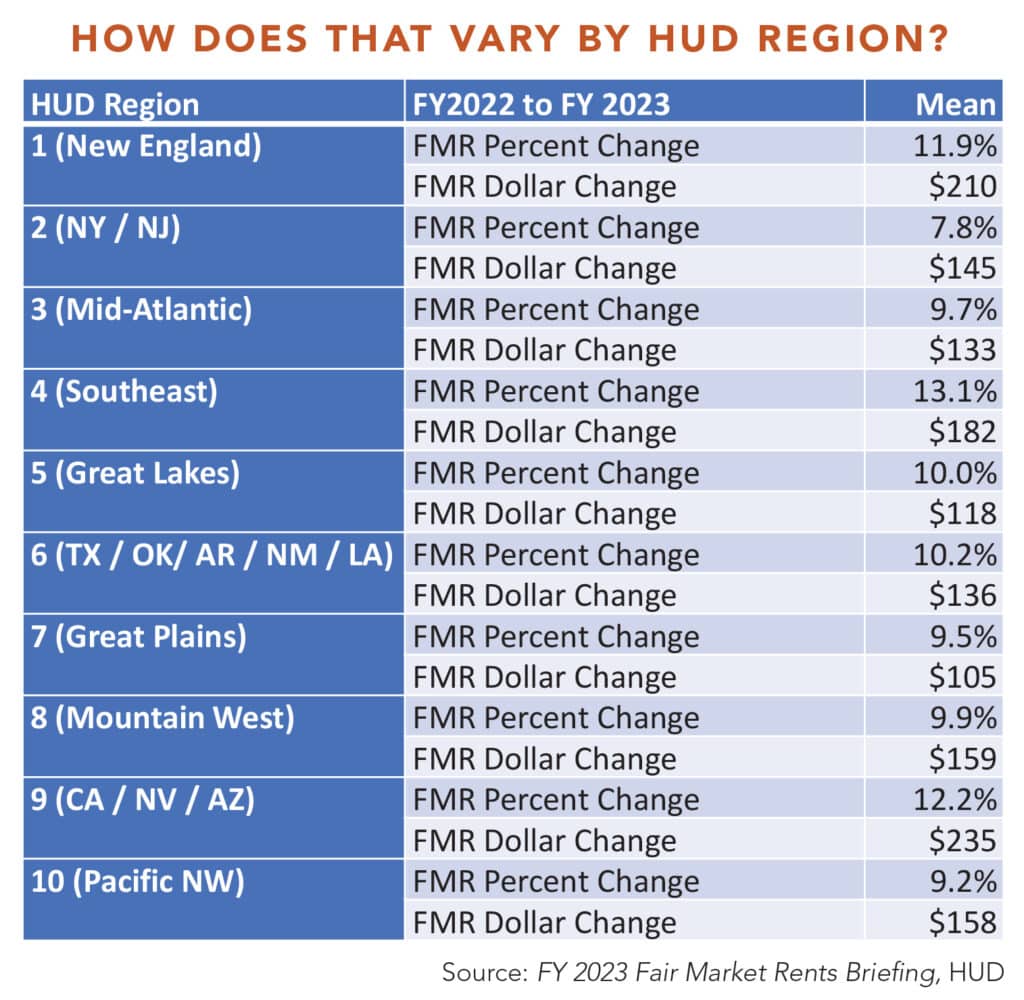

FMRs for 2023 increased over the last year by around ten percent in nearly all regions, Stagg says, whereas the prior year had a typical increase of under three percent.

HUD’s data show that the Southeast had the highest increase, at over 13 percent, followed by California, Nevada and Arizona at just over 12 percent. On a metro level, Salinas, CA and Phoenix saw the highest FMR growth, while Florida and Alabama metros grew substantially also.

“It’s a big increase, but I think if you ask people, it was much needed,” says Stagg, reflecting on how market realities drove up FMRs. “Fair market rents have been lagging behind what we’ve been seeing in the market; but when they accurately reflect renting conditions, it increases the housing [supply] that tenants can move into.” But Stagg cautions that this does not necessarily make higher FMRs beneficial. “We want them to just keep up with the market.”

“The main consequence of a decreased FMR is that when we have project-based vouchers in our affordable housing projects, the amount of rent that the owner can collect goes down, which hurts our projects,” says Ely. HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge made a similar point once the 2023 FMRs were released saying, “One of the reasons that housing voucher holders are unable to use those vouchers is because the value of their vouchers has not kept up with rapid rent increases.”

Stagg, however, notes that in some parts of California, in particular, the rate of FMR growth has slowed, thanks to decreased demand amidst COVID. HUD finds that San Francisco’s FMR declined 0.3 percent. “You can see For Rent signs in windows in San Francisco,” says Ely. “I haven’t seen that in 23 years.” (The San Francisco-Oakland residential vacancy rate jumped 63 percent from 2021 to 2022.) Ely says that for this reason, “we were not up in arms when we got the reduced FMRs.”

However, cities like New York and San Francisco were the exception, since their dense layout made them undesirable during the pandemic. Overall, rents have increased nationwide by 17 percent year-over-year as of March 2022, due to the housing shortage and inflation. In Housing USA: Higher interest rates and affordable housing (Tax Credit Advisor October 2022), we explained why rent increases might continue even as the housing market dips – because when high-interest rates discourage people from homebuying, they rent instead.

So far, the rental price increase has caused a broad increase in FMRs, and the National Center for Housing Management claims these increases are necessary to meet market conditions. “Rents commanded by private landlords have been above how much the Public Housing Agency is able to pay, which renders the voucher essentially useless in many markets.”

This raises the question of whether HUD’s standard methodology is the best way to calculate FMRs. Reporting lags can impact the ability of FMRs to accurately reflect market conditions. The aforementioned private data was introduced to shore up these informational gaps.

“It’s helpful to have that kind of snapshot of time,” Stanley notes, comparing the ability of private sector aggregators to provide “comparisons to rent month-to-month” as opposed to the longer lead time needed with Census data.

Ely concurs, recounting one time recently that San Francisco and other Bay Area cities performed a joint reassessment. “All the Bay Area housing authorities got together and said…’the data that HUD’s putting out is not realistic.’” This reassessment at one point triggered a 30 percent increase. However, a similar study last year did not lead to an FMR boost.

“I wouldn’t say that they’re pushing back against HUD, but it’s a data exercise,” she concludes. “Our Housing Authority is on its way to maxing out that wiggle room” of a ten percent FMR increase.

In any event, the degree to which Low Income Housing Tax Credit projects would be impacted by decreased FMRs is limited by the “hold harmless” policy. This ensures that the floors on rent and income cannot drop. This determination is ultimately made by calculating area median gross income (AMGI), a separate measure.

The use of private data for determining FMRs represents a substantial change from past practice. And the upward trend of rental prices suggests that past methods may not have been the best way to capture market conditions. While the measure is temporary, it may be worth monitoring private data more extensively in the future. “Historical data…has its use,” says Stanley, “but it’s not always the timeliest, most impactful or most accurate for what our residents are actually facing.”

This article featured additional reporting from Market Urbanism Report content manager Ethan Finlan.