Local Preservation Tools

By Mark Olshaker

13 min read

There is no argument that affordable and subsidized housing is under strain and in many areas, finding land and launching new building projects is increasingly problematic. It is therefore crucial, most industry watchers and insiders agree, to preserve the existing residential stocks in the various programs, and to bring neglected and at-risk properties up to desirable levels.

The question is: How?

TCA asked three experts what local tools they have used to create development opportunities while serving at-risk properties. While each possible solution is intricate and not without its own potential downsides, each has worked effectively on the local level and offers a model for how other jurisdictions can preserve housing affordability with existing buildings. Many of those jurisdictions are already looking closely at the results. Readers Warning: Many acronyms lie ahead.

Preservation Challenges for Massachusetts

Massachusetts has some of the most difficult affordable housing issues, due to high urban rents and scarce land availability. To address this, the commonwealth has some of the most forward-thinking and successful programs in the nation. Make no mistake, though: The challenges to these programs are large and ongoing, requiring creative solutions.

Five years ago, SHARP (State Housing Assistance for Rental Reduction Program) was in financial danger. MassHousing decided the best course was to let owners leave the program, and in so doing, it collected enough debt in aggregate to pay off the bonds that supported it. “All the properties were right-sized and we found MAP (Multifamily Accelerated Processing) approved lenders to make the loans,” states Karen Kelleher, MassHousing’s deputy director. “Essentially, we subordinated our debt and took a cash flow note and preserved these properties with almost no exceptions, in perpetuity. That’s about 1,300 units that have now been preserved as a result of a really creative negotiation between the owners and the agency to find a creative financing solution that would get the properties where they needed to go.”

During Fiscal Years 2016 and 2017, approximately 10,000 existing apartment units financed through MassHousing were in danger of having their affordability expire in three to five years. “We did two things,” Kelleher recalls. “We altered our prepayment policies to let [owners] find a way to prepay early or to do a refinance. We required them to refinance with us, but we got very competitive on our lending products. As a result, over the last two years we have done about 10,000 units that would have had the right to go and do a MAP financing that wouldn’t have had affordability restrictions. We wanted to keep those properties in our portfolio if we could.”

Section 13A of Part II, Chapter 186 of Massachusetts General Laws, is the commonwealth’s version of the HUD Section 236 Rental Assistance Program, with a state mortgage interest rate subsidy on projects providing low-income and affordable housing that reduces the owner’s rate to one percent. Savings are passed on to the resident through a reduced, budget-based rent (basic rent). The basic rents are well below both market and Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) levels and are aimed at what MassHousing characterizes as an extremely vulnerable resident population for which the average household income is $26,000. Nearly 90 percent of households earn below 60 percent of Area Minimum Income (AMI) and nearly 25 percent earn below 30 percent.

This portfolio is the one most at risk today, according to Kelleher.

Starting in 2004, the commonwealth began reducing its funding commitment to the program and stopped completely in 2009. MassHousing addressed the appropriations gap by picking up the obligation of about $80 million. Until 2013, long-term preservation was expected to be achieved with federal Section 8 vouchers, but then federal resources became unavailable, preservation became a challenge, and deep affordability was harder to achieve. That left about 3,300 units in 34 properties at risk, with affordability mandates expiring between 2017 and 2020.

Several steps and resources have been brought to bear to address this. Massachusetts Rental Voucher Program (MVRP) payments have been increased to LIHTC levels from the state Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD). This amounts to more than $6 million annually. There is a priority for the tax-exempt volume cap, more than $350 million annually. MassHousing and DHCD are each providing $50 million in soft debt, DHCD through bonds and MassHousing through its Opportunity Fund, plus the remainder of the $80 million interest rate subsidy from MassHousing. Resources are generally rolling and Boston and other municipalities are committing local funds.

Given the unique challenge of the 13A portfolio, MassHousing’s approach is responsive to the risk of market-rate conversion, and the potentially severe impact on tenants. The agency is therefore:

- Calculating a proxy for an achievable market sales price for all remaining 13A properties;

- Estimating how much of that sales price could be addressed with new first mortgage debt;

- Making credible subsidy offers sized to make owners “whole;” and

- Linking tax credit equity resources more directly to capital needs.

Preservation efforts are already bearing fruit. Four properties containing 194 units will be preserved by the end of 2017; ten properties containing 1,127 units will likely be preserved by the end of 2018; three properties with 195 total units will likely be preserved by the end of 2019; and eight properties with 1,199 units have the potential to preserve, but the outcomes are uncertain. Additionally, nine properties with 468 total units have not engaged in preservation planning and their outcomes are even less certain. The state will continue to work toward preservation, but it is estimated that at least half of these properties will likely convert to market-rate. Unless an owner is willing to consider preservation, or offers the property for sale, the state has no legal ability to preserve its affordability.

“There is no one solution,” Kelleher summarizes. “The way we are trying to divvy up a limited pool of resources is to really focus on the acquisition price. We estimate how much of the sales price could be covered by a first mortgage. The gap is roughly what the subsidy offer would be. It’s more complicated than that, but that’s the basic principle. To the extent that the property needs capital work, the source for that would be essentially volume cap, four percent tax credits.” She notes that like many states, Massachusetts has cap constraints, so there are limitations. She says there is a range of typical owners for 13A properties, mostly in the for-profit sector.

“The interesting thing from a public policy perspective is that MassHousing recognized that there was a problem. They recognized also that ‘playing possum’ was the solution for a lot of owners,” says Bill Brauner, director of housing preservation and policy of CEDAC, the commonwealth’s Community Economic Development Assistance Corporation. “And so they said, ‘Let’s go make offers.’ You know, that’s pretty proactive for a state agency to say, ‘Let’s go assemble resources and we want to do it now, and facilitate action because otherwise [affordable housing] will go away.’”

“That was the idea,” Kelleher confirms.

Chapter 40T: Right of Offer

“In Massachusetts, preservation is the default option. A lot of creativity has gone into how we make this law work in practice,” Brauner comments. The law he refers to is Chapter 40T of Part I, Title VII of Massachusetts General Laws, enacted in late 2009. “In the first five years of 40T, we preserved eight projects totaling 1,074 units with the right of offer and first refusal, and 62 projects totaling 5,034 units, with exempt sales. Several high-profile 13A and Section 236 Right of Offer and Right of Refusal projects have closed in 2017, with more 13A projects in process.”

Those two provisions are at the heart of the law, which covers 16 housing funding programs, including 13A, Section 236, project-based Section 8 and LIHTC. Not covered are 40B, Home Investment Partnership (HOME), Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), Affordable Housing Trust Fund (AHTF) and Housing Stabilization Fund (HSF) programs.

The power of 40T rests on three legs: notice of upcoming termination, right of offer and right of first refusal and tenant protections.

The notice requirements are quite specific. If a project is to be put up for sale, the owner must provide tenants, tenant organizations, CEDAC, DHCD and local legal services organizations with a notice of future termination of affordability (Notice of Intent to Sell) two years in advance. One year in advance, the owner must file a notice to complete termination.

Any termination notice triggers the second provision. Upon a Notice of Intent to Sell, DHCD can assign rights to a Prequalified Preservation Buyer, which can be an experienced nonprofit or for-profit affordable housing provider. For 90 days following the notice, the owner cannot accept any offer except from DHCD or its designee, though the owner is not required to accept such an offer. “Most 40T transactions are preserved at this stage,” says Brauner.

After a right of option period, the owner can agree to a sale to a third-party buyer. But with the right of first refusal, the tenant association or DHCD designee can “step into the shoes” of the third-party buyer on the same terms, with the added protections of a 90-day refundable deposit of no more than two percent of the sales price, up to $250,000, and closing no sooner than 240 days.

Recognizing the aim of preserving affordability, sales that preserve it for at least 30 years are exempt from the rights of offer and first refusal. So are instances of eminent domain, foreclosure and affiliate sales. As for tenant protections, low-income residents who do not receive enhanced vouchers are protected for three years after termination and rents cannot be increased by more than the Consumer Price Index plus three percent per year.

As one might expect with such a comprehensive approach, there are complications. Aside from the fact that several important housing programs are not covered, acquisitions are at market-rate, and have to compete against third-party commercial investors, particularly in dense and desirable urban areas, which can drive up prices. Also, the right of first refusal is not a right to purchase.

And there is one loophole, says Kelleher. “When an owner wants to go market-rate but not sell the property, the only protections tenants have are the rent protections the law provides.”

Yet the results speak for themselves. “In 2018, we have 300 units [so far] that are likely 40T deals,” Brauner says. “The state has really stood behind its designees in helping deals to close.”

“Of the properties that have triggered 40T,” Kelleher notes, “in the first five years of the program every one of them was preserved. And in the subsequent two years, only one small property was lost.”

Tenant Opportunities in the Nation’s Capital

“The Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act [TOPA] in DC is not a preservation tool but an anti-displacement tool,” declares William “Bill” Whitman, owner and managing partner of New Community Partners LLC. Yet TOPA, enacted in 1980, has become an important weapon in the arsenal of preservation tools for the nation’s capital, along with the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF, to which Mayor Muriel Bowser pledged $138 million for 2018), inclusionary zoning, HOME and CDBG funds, DC Rental Housing Supplement and the Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP).

Similar in many ways to 40T, TOPA provides duly organized and registered tenant associations (TAs) the opportunity to match third-party contracts to purchase buildings with more than five units. Tenants have 30 to 45 days to file a notice of intent to match, 120 days to negotiate a matching purchase contract, and 240 days to close, with added consideration for due diligence delays.

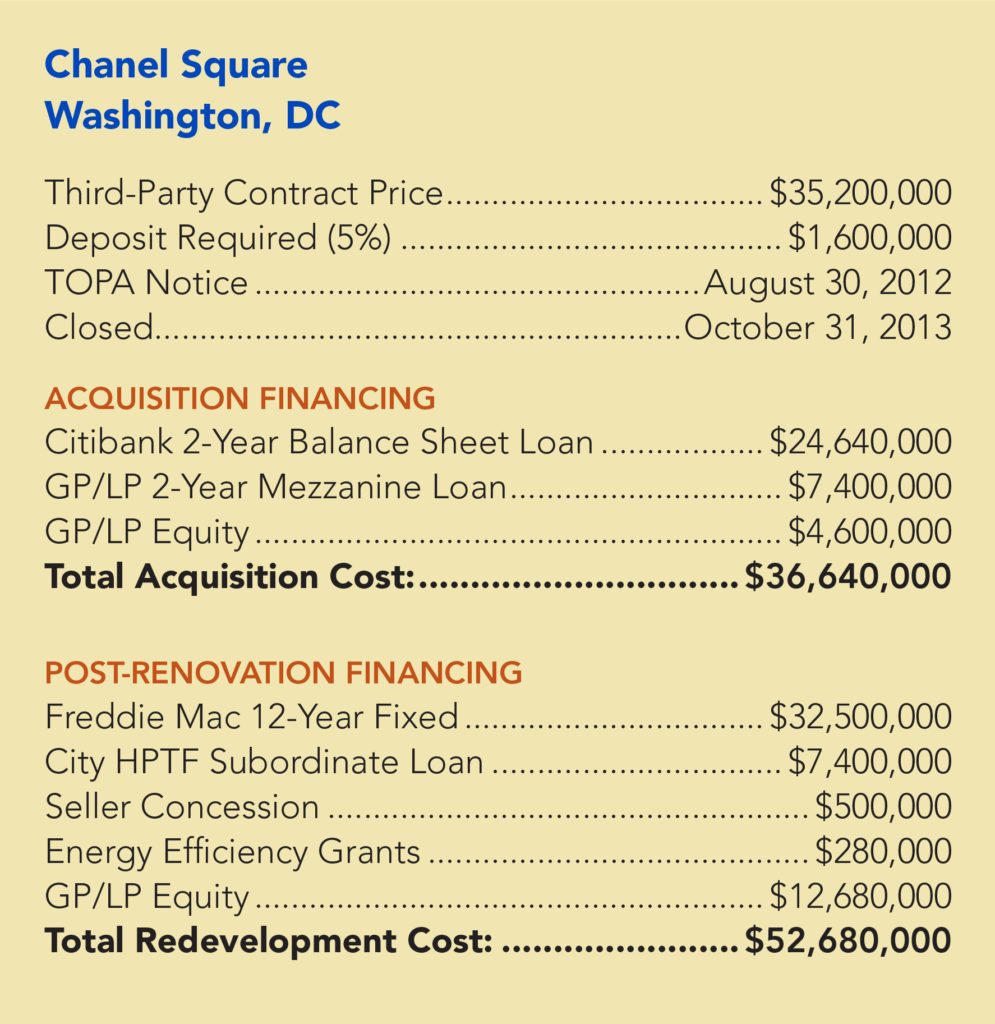

As an example of TOPA’s utility, Whitman cites Channel Square, a five-building complex in Southwest Washington (See Pinpointing the Need for Workforce Housing in the January 2017 issue). It was designed by famed Chicago architect Harry Weese, who also designed the nearby Arena Stage and the DC Metrorail system stations. The project was built in 1967 under HUD 236 as part of DC’s massive Southwest Urban Renewal effort. Channel Square had evolved into a mixed-income community of about equal thirds rent control, vouchers and market-rate. The location had become a prime one, between Nationals Park baseball stadium and the new waterfront development, but it was in serious need of rehab.

The Dutch pension fund that owned it put it on the market with the idea of adding value by splitting the units in half, which terrified the residents, particularly those with large families. When a third-party contract price of $35.2 million ($158,000 per unit) was announced, the TA filed notice, interviewed “go-to” affordable housing developers, and assigned purchase rights to a general partnership of New Community Partners, Somerset Development Company and the National Housing Trust/Enterprise Preservation Corporation. “The tenants were looking to preserve the affordability, not private gain,” says Whitman.

The developers pledged to preserve affordability at one-third of units below 50 percent of AMI, one-third below 80 percent, and one-third market-rate – basically the mix at the time of sale. The developers would upgrade the property, endow a tenant service program with $100,000 and share 15 percent of their cash flow for resident services. The affordability covenant lasts 40 years.

“We could not use LIHTC because we could not force existing tenants to income-certify,” Whitman notes. The group spent two years putting together rehab specs and putting a permanent Freddie Mac loan in place. The rehab involved refinishing all common areas and covering the roof with photovoltaic panels.

“City funding is now closely aligned with the TOPA process,” Whitman says. “It preserves existing stock and minimizes tenant displacement. Most of the time, additional costs are absorbed by public subsidies.” Like other tenant-option arrangements, he concedes that it can add costs as developers push for higher prices.

State, County and City

Brauner notes that innovative laws and regulations are currently being enacted on the state, county and city levels.

In Massachusetts, a bill is before the legislature modeled on TOPA. Massachusetts also offers a donation tax credit that Brauner says “was copied from Illinois, copied from Missouri,” and which he calls “one tool that is tremendously helpful for people to capture the market value of properties and get a subsidy for them, particularly in communities where you’ve got lots of value.” Then, “in Oregon, in three months they got their own right of first refusal bill through the legislature and signed by the governor.

“Montgomery County, MD has a very effective opportunity to purchase act. The right is first exercised by the county, then by the Montgomery Housing Opportunities Commission, and then the tenants. [Neighboring] Prince George’s County has something similar.

“And Denver is working on a housing preservation ordinance with a lot of 40T characteristics.”

As Karen Kelleher suggests, there is no one solution, and none of these programs is without drawbacks. But need and legislative creativity are combining to preserve housing affordability in some areas where market challenges are the greatest.

Story Contacts:

Bill Brauner

[email protected]

Karen Kelleher

[email protected]

William Whitman

[email protected]