Subsidizing the Middle: Policies, Trade-Offs and Costs of Addressing Middle-Income Affordability Challenges

Report Analyzes Impact of Subsidizing Housing for Middle-Income Earners

By Pamela Martineau

5 min read

As an increasing number of cities and states throughout the nation develop a broad range of programs to subsidize housing for middle-income earners, policymakers need to ensure that these middle-income programs don’t take vital resources from low-income housing programs, yet still help ease the cost burden of housing in the middle.

That was a top-level takeaway from a July report from Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) titled: Subsidizing the Middle: Policies, Trade-Offs and Costs of Addressing Middle-Income Affordability Challenges. The report, authored by Alexander Hermann, Whitney Airgood-Obrycki, Nora Cahill and Peyton Whitney, also cautions against using the term “workforce housing” to describe middle-income housing.

“The term “workforce housing,” which can be taken to imply that people with lower incomes do not work, also further marginalizes lower-income households and perpetuates stigmas against affordable housing that serves them,” the report states.

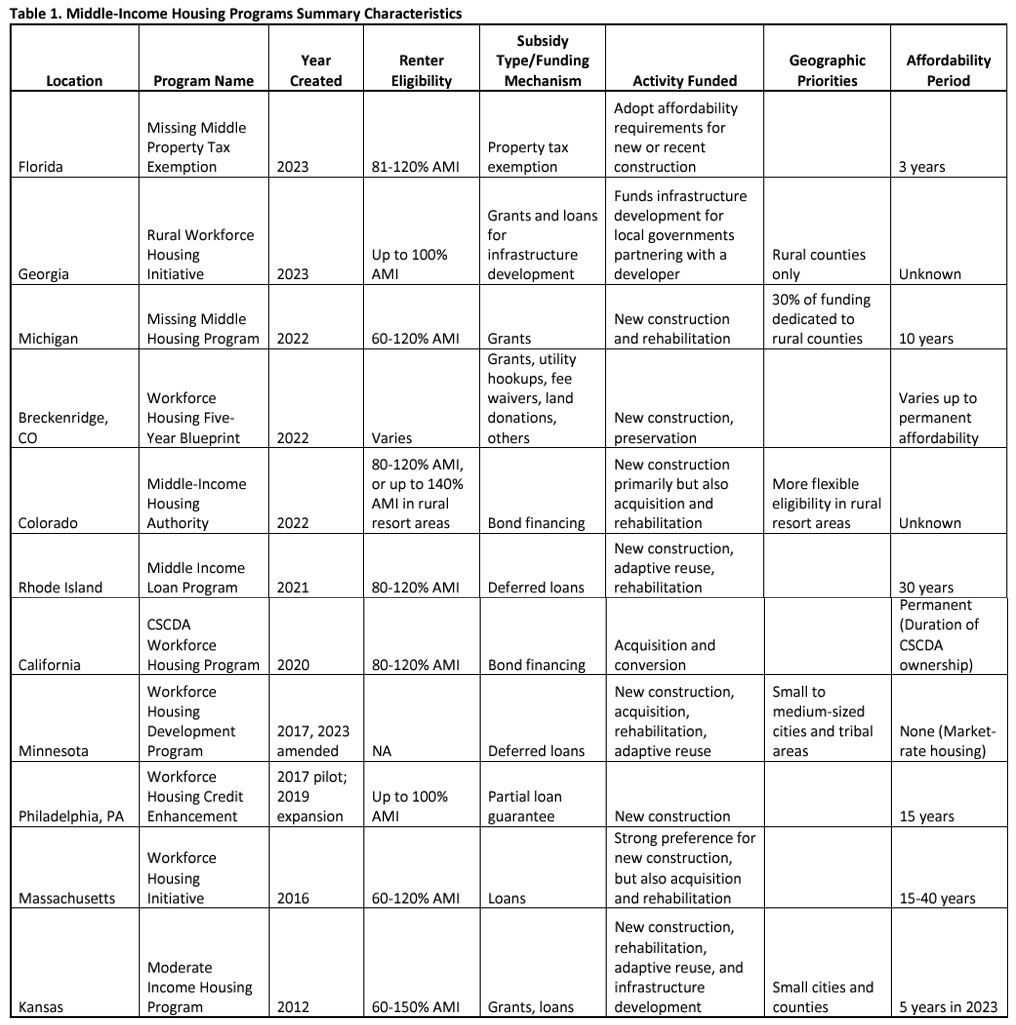

The report highlights various middle-income housing programs throughout the nation, outlining their target populations and varied efforts to spurn the development of middle-income housing stock.

“These middle-income housing programs differ tremendously in terms of their funding mechanisms, activities and requirements, but we highlight ten key themes,” the press release announcing the JCHS report states. “For starters, these programs are relatively new, with most of them coming into existence in 2019. The programs are geographically diverse, present in states across the country and encompass a range of market conditions, housing costs and political environments, including statewide programs in California, Georgia and Minnesota.”

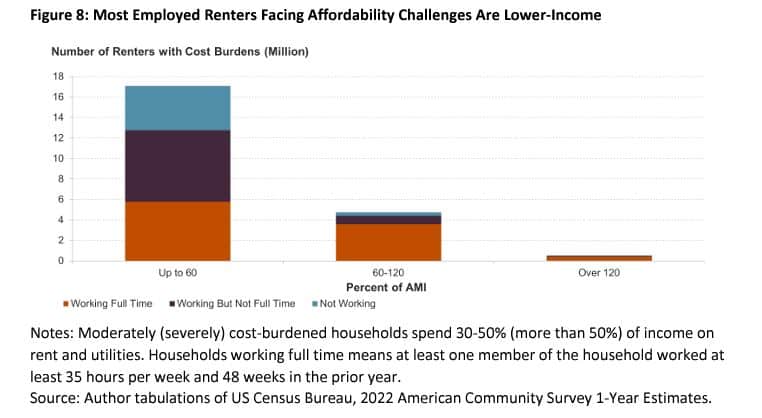

Housing Cost Burden Is Highest Among Low-Income Earners

The report outlines how “housing affordability challenges have crept increasingly up the income scale and have left a record-high share of middle-income renter households with cost burdens.” This reality has resulted in states and local governments developing programs to address middle-income housing needs.”

“These (middle-income) programs hold some promise for expanding the supply of affordable housing, especially in places with severe affordable housing challenges or in difficult-to-develop areas, but they face backlash from housing advocates who fear these subsidies will redirect resources away from lower-income households with the greatest need,” the report states.

According to the report, various programs in the United States currently spend roughly $160 billion annually to provide housing for low-income people. By comparison, roughly $28 billion a year is spent on housing programs for middle-income earners. Despite the difference in spending on target populations, the report states that monies diverted from lower-income programs could have a more hurtful impact on lower-income people. Lower-income households tend to suffer a greater cost burden for housing since they have less money left after paying rent to pay for other basic needs, the report highlights.

“Middle-income earners are also disproportionally white, which raises concerns about reinforcing racial inequities,” the report continues.

The Need for Middle-Income Housing Programs Remains Strong

Still, the need for middle-income housing programs remains strong, and cities and states throughout the nation are coming up with creative solutions. The study that spawned the report examined 11 state and local programs that seek to bolster housing for middle-income earners. The report defines middle-income households as those with household incomes between 60 to 120 percent of the area median income (AMI). Eligibility for middle-income programs varies with lower limits hovering between 60 and 120 percent AMI and higher limits at about 100 to 150 percent AMI.

“Several broad commonalities unite these programs,” the press release on the study from JCHS states. “Nearly all use a percent of AMI threshold to determine eligibility, rather than employment status, occupations or some other criteria, even when they are specifically billed as ‘workforce housing’ programs. While some programs fund rehabilitation, adaptive reuse or acquisition and conversion, they largely emphasize new construction.”

Some unique middle-income programs include the Michigan Missing Middle Housing Program, which was created in 2022 with American Rescue Plan Funds. The program provides grants to developers to build or substantially rehabilitate properties that are kept affordable for households making between 60 to 120 percent of AMI. The grants are intended to cover labor and material costs for the construction of rental and for-sale housing. Some 30 percent of the program funds target rural areas, and the program requires income verification for a ten-year compliance period.

The Massachusetts Workforce Housing Initiative provides low-interest loans to developers to construct or reuse rental projects targeting households in the 60 to 120 AMI range. Some 20 percent of the units in those projects also need to be affordable to household earnings at or below 80 percent of AMI.

The Rhode Island Middle Income Loan Program, created in 2021, also provides low-interest rate loans to finance the construction of middle-income for-sale or rental housing targeting households making 80 to 120 percent of AMI.

In Florida, state leaders developed a property tax exemption program in 2023 for projects targeting households in the 80 percent to 120 percent AMI range. Colorado’s Middle-Income Housing Authority program, developed in 2022, provides bond financing for new construction, acquisition or rehabilitation of projects targeting households in the 80 to 120 percent of AMI range, and 140 percent of AMI in resort areas. A local program in Breckenridge, CO, called the Workforce Housing Five-Year Blueprint, developed in 2022, provides grants, utility hookups, fee waivers and land donations for new construction or preservation of projects for varying income levels of renters.

The Georgia Rural Workforce Housing Initiative provided roughly $24 million in infrastructure grants to local governments to help the construction of about 1,000 units of housing that target middle-income earners. In Kansas, the Moderate-Income Housing Program provided roughly $27 million in funding for developing 992 rental and for-sale housing units in 2023 alone, costing about $27,000 per unit.

Few Studies Exist on Middle-Income Programs

The JCHS press release announcing the middle-income housing report states that because of “their relative recency minimal research has been done on state and local middle-income housing policies and programs.” The study and report seek to “close this gap by documenting the rise and features of these programs.

“Their proliferation speaks to the growing unaffordability affecting more people and more places than ever before,” the press release continues. “However, the cost of addressing middle-income affordability must be balanced with meeting the long-standing and deep needs of lowest-income renters.”