When the Exactions Go Too Far

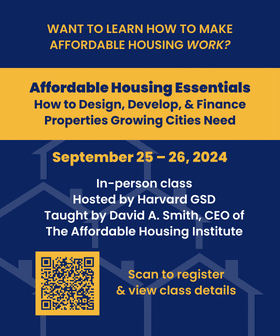

By David A. Smith

5 min read

Are you an affordable housing developer in search of a local building permit and feeling helpless as popup financial exactions materialize as fast as you vanquish the previous ones? Now there’s one weird trick you can use to get relief: say “sheetz.”

Barely a month ago, the Supreme Court ruled that “the Takings Clause prohibits legislatures and agencies alike from imposing unconstitutional conditions on land-use permits.” By doing so, the Court planted yet another stake defining the ever-more-fractal boundary of a century-old land-use law question: how far can local government’s urban planning go?

Invented in the Roaring Twenties, American urban planning is a century-old political game that kicked off with two goalpost decisions:

- 1922’s Pennsylvania Coal established that regulation depriving an owner of all economic value of his property is compensable under the Takings Clause; and

- 1926’s Village of Euclid held that “zoning ordinances are constitutional under the police power of local governments as long as they have some relation to public health, safety, morals or general welfare, and are not arbitrary or unreasonable.”

Unreasonable, you say? Urban planning unleashes the Four Horsemen of local land power – zoning, permitting fees and procedures, infrastructure financing and eminent domain. These horses must be harnessed together because without them affordable housing is impossible. Modern cities are technological and vertical, and these require utility infrastructure – transportation, water and sewer, power, electricity and broadband. Every utility network represents a huge capital investment, most of it financed by the government. Once put in place, the network is both a sunk capital cost and a wellspring of revenue. It creates latent development value that then is activated by the risk-taking private sector, with the proceeds being shared back to the private sector through increased taxes – real estate, business, sales and income.

Properly done, this is a symbiotic balance: planning and public investment enable cities to rise, and rising cities repay both the private property capital and the public investment. All it takes is a balanced and long-sighted urban policy.

That’s easier said than done. Voters are often self-interested, short-sighted and happy to spend the public’s money. Public officials are often self-interested, short-sighted and happy to spend the voters’ money. Hence the urban planning paradox: the bigger, more complex and richer the city grows, the more it needs disinterested urban planning and yet the less it gets, as urban planning is kidnapped and fought over by a squabbling mob of special interests.

The Supreme Court foresaw this when it drew the abstract line: “If regulation goes too far, it will be recognized as a taking.” Over the ensuing century, the Court has drawn lines:

- For public-benefit limitations as in Penn Central (1978; designating Grand Central Station a landmark did not destroy all value or current use); and

- Against approval extortions, such as in Nollan (1987; concede a public beachfront to build a small house) and Dolan (1994; build a bicycle pathway to expand a store).

In response, local officials became more innovative in camouflaging their exactions.

Enter California retiree George Sheetz, who wanted to build a home on property he’d bought several years earlier. In 2016, El Dorado County ordered him to pay a $23,420 ‘traffic impact fee’ for the privilege. Under protest, he paid, built his home – and sued, citing Nollan and Dolan. The California district court and then appellate court ruled, imaginatively, that Nollan and Dolan applied only to ad hoc decisions, not to “a fee like this one imposed on a class of property owners by Board-enacted legislation.” Nearly eight years later, the Supreme Court, in a 9-0 curb-stomping, ruled that the Takings Clause “does not distinguish between legislative and administrative land-use permit conditions.” Justice Gorsuch punctuated this with a pithy concurrence, “whether the government owes just compensation for taking your property cannot depend on whether it has taken your neighbors’ property too.”

This matters a lot for affordable housing. All too frequently, those reviewing make the developer undertake ‘mitigation’ to placate the permanently loud anti-everything bloc or to treat some other constituency to a ‘community benefit’ on the political reasoning that ‘it’s affordable housing, they’ll find the money somewhere.’ Affordable housing seems so expensive because it’s carrying a horde of free riders. Knowing this, developers hold their noses, squelch their moral outrage, pay the exactions…and smile sickly. Now, at least, they can mutter, “sheetz.”

The game is far from over. Though the decision “[sets] the stage for widespread lawsuits contesting the constitutionality of the many billions of dollars in impact fees developers are forced to pay annually to get construction permits,” as two Holland & Knight attorneys percipiently noted, the line between reasonable and too far still blurs. The case yielded three ‘yes but’ concurrences, including one (from the unlikely trio of Justices Kavanaugh, Kagan and Jackson) observing that the Court has yet to rule on “the common government practice of imposing permit conditions, such as impact fees…based on reasonable formulas or schedules that assess the impact of classes of development.”

‘Reasonable?’ They keep using that word: I do not think it means what they think it means.